The Spirit of MLK Lives On at Eastside

January 16, 2020

In 2020, Denver Health is celebrating 160 years of providing care for all in the Denver community. As we reminisce we are reflecting on our rich history and some of the people we have cared for, including historical figures who passed through the mile high city. All year long, we will be sharing some of the stories that make up 160 years of care in the heart of Denver.

Nearly 160 years ago, the predecessor of Denver Health was founded in a rough-hewn building in downtown Denver near the intersection of Wazee and 16th Streets. Its name was City Hospital and its mission was remarkably similar to the modern-day Denver Health: To care for the sick and the injured and the poverty-stricken.

Denver was a lawless outpost at the time, and was made up largely of gambling dens, brothels and saloons. “As you wander these hot and dirty streets you seem to be walking in a city of demons,” recalled one settler. “In these horrible dens a man’s life is of no more consequence than a dog’s.”

That Denver had a hospital at all was an amazing accomplishment. There were no roads, no schools and no government. There were also no medicines to combat diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid and smallpox. The early pioneers knew that sickness often led to death and a hospital must have been considered a basic necessity.

City Hospital struggled to stay afloat and closed after only a couple of months of operation. One of the founding surgeons joined the Union Army and the other surgeon switched to brokering gold dust, bankrolling mule trains and running stage coaches. Patients were taken care of in makeshift facilities across the city for the next few years.

By 1873, a new hospital building resembling a two-story house was established at 6th Avenue and Bannock Street. This location has been Denver Health’s home ever since.

Denver Health has grown up alongside the city, enjoying the same good times and suffering the same hard times. It has consistently received strong support from city and state leaders, as well as the people of Denver themselves, who have approved bond issue after bond issue to modernize and grow the hospital.

Currently, a new Outpatient Medical Center is being erected at the corner of Bannock St. and 7th Avenue, a stone’s throw from the location of the 1873 hospital.

Denver Health has expanded far beyond its original geographical borders. Located around the city are some nine Family Health Centers, with a 10th scheduled to be opened in June. There are also 18 School-based Health Centers, five urgent care centers and several health centers, which are in partnership with other nonprofit or governmental entities. The health centers are modern, well-equipped and at the heart of their communities. They would have shocked those early pioneers.

The oldest in the network of health centers is the Eastside Family Health Center, located in the vibrant Five Points neighborhood. Denver Health officials recently invested $6.2 million in renovations there. The lobby is bright and welcoming, the hallways and exam rooms are immaculate, state-of-the art exam tables have been installed and dozens of solar panels adorn the roof.

But the pent-up demand for affordable healthcare was enormous, particularly in the Five Points area, which was considered the poorest of Denver’s inner-city neighborhoods. “All of a sudden in the first two weeks, they’re seeing 2,000 patients. And in the first month, it’s 20,000 patients,” Castro said.

In 2006, Denver Health added the name, Bernard F. Gipson Sr., to Eastside’s official name. Dr. Gipson was the first board-certified black surgeon in Denver and considered to be a giant in his field.

Dr. Gipson never actually worked at Eastside, but officials at Denver Health added his name to the clinic to honor him, recalled his son, Bruce Gipson.

Dr. Gipson dreamed of becoming a doctor when he was a young boy growing up in Bivins, Texas, where Jim Crow laws were strictly enforced. He was the son of a single mother and one of 10 siblings. He studied by kerosene light, nursing his dream and eventually obtained his medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine.

Dr. Gipson arrived in Denver in the early 1950s as a captain in the U.S. Air Force and chief of surgery at Lowry Air Force Base. When his military tour was completed, he decided to make Denver his home.

Dr. Gipson struggled to obtain referrals and met with opposition from white doctors when he tried to open a practice at 18th and Gilpin St. The physicians were willing to accept one black physician in their midst, but not more than one. “It was much more openly racist back then,” his son said. “A surgeon needs referrals and he was not getting the referrals he needed.” His father became a sort of country doctor, oftentimes accepting poultry in lieu of money.

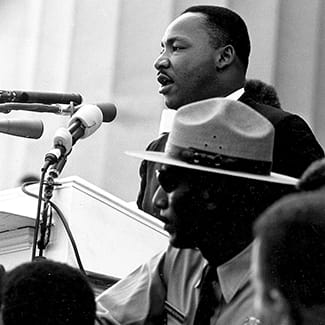

Two of Dr. Gipson’s most famous patients were Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King. Dr. Gipson treated them both when they were in Denver. “Both of them had minor issues regarding altitude,” recalled the younger Gipson. Dr. Gipson’s waiting room was often filled with elderly female patients and when his father strode through one day with Martin Luther King, “he probably had to pick them up off the floor,” his son said.

Martin Luther King and his wife, Coretta, began sending Dr. Gipson their annual Christmas letters. In a letter dated December 1967, only a few months before Dr. King was assassinated, Dr. King’s message was filled with hope and optimism. “This is a season when we can still take heart. We can be joyful that swelling masses are absolutely dedicated to the death of racism and a life of brotherhood.” Read the full letter here.

Dr. King was in Denver several times during the 1960s. He gave speeches at the University of Denver, preached at several churches, and met with local leaders and dignitaries.

Among them was former Denver Mayor Tom Currigan, who was a great supporter of Denver Health, and persuaded the Office of Economic Opportunity to give Denver a demonstration grant of $805,500 to establish Eastside, the second such clinic in the nation and the first to open in an urban area.

Dr. Gipson’s portrait and Martin Luther King’s 1967 Christmas letter hang on the wall near the pharmacy on the first floor of the Eastside Health Center. Many of the patients are too preoccupied or sick to notice the letter. But if they do happen to look up and read a few sentences, their spirits might be buoyed.

Dr. King writes of a world on the verge of overcoming poverty and racism and violence, but warns that much work still needs to be done.

“We, these people, you, all of us – must have not only hope for the unknown future, but also confidence in our capacity to change the menacing present. Let us put hands and heart, mind and muscle, to this task. Let us not give up, for surrender and apathy are nothing but failure. In our work, let us see scorn and ridicule of us for what they are – scornful and ridiculous.”

Read more stories celebrating Denver Health's 160th anniversary.